At the Hong Kong Jewellery Sept 2025, one huge banner summed up the market in five words:

“Pay for the gold, the lab diamonds are free.”

The message was clear. Lab-grown diamond prices have collapsed due to oversupply. A one-carat D-colour VS stone could be bought for under US$80, a two-carat for less than US$300. When the diamond becomes cheaper than the gold that holds it, fine jewellery loses its balance — the precious metal carries the value, while the stone does not.

For artisan and artistic jewellers such as Vermilion, this makes the path clear: lab diamonds have no place in fine jewellery. They may have their uses in costume jewellery, training, or experimental design, but they cannot carry the weight of permanence, heritage, or artistry.

The New Era of Detection

Until recently, one of the greatest concerns for jewellers was the possibility of lab diamonds entering the supply chain disguised as natural stones. Now, inexpensive hand-held probes make it simple to tell them apart in seconds. What once required sending a stone to a gemmological laboratory can now be done over the bench with certainty, whether it be simulant, CVD/HPHT (lab) or natural.

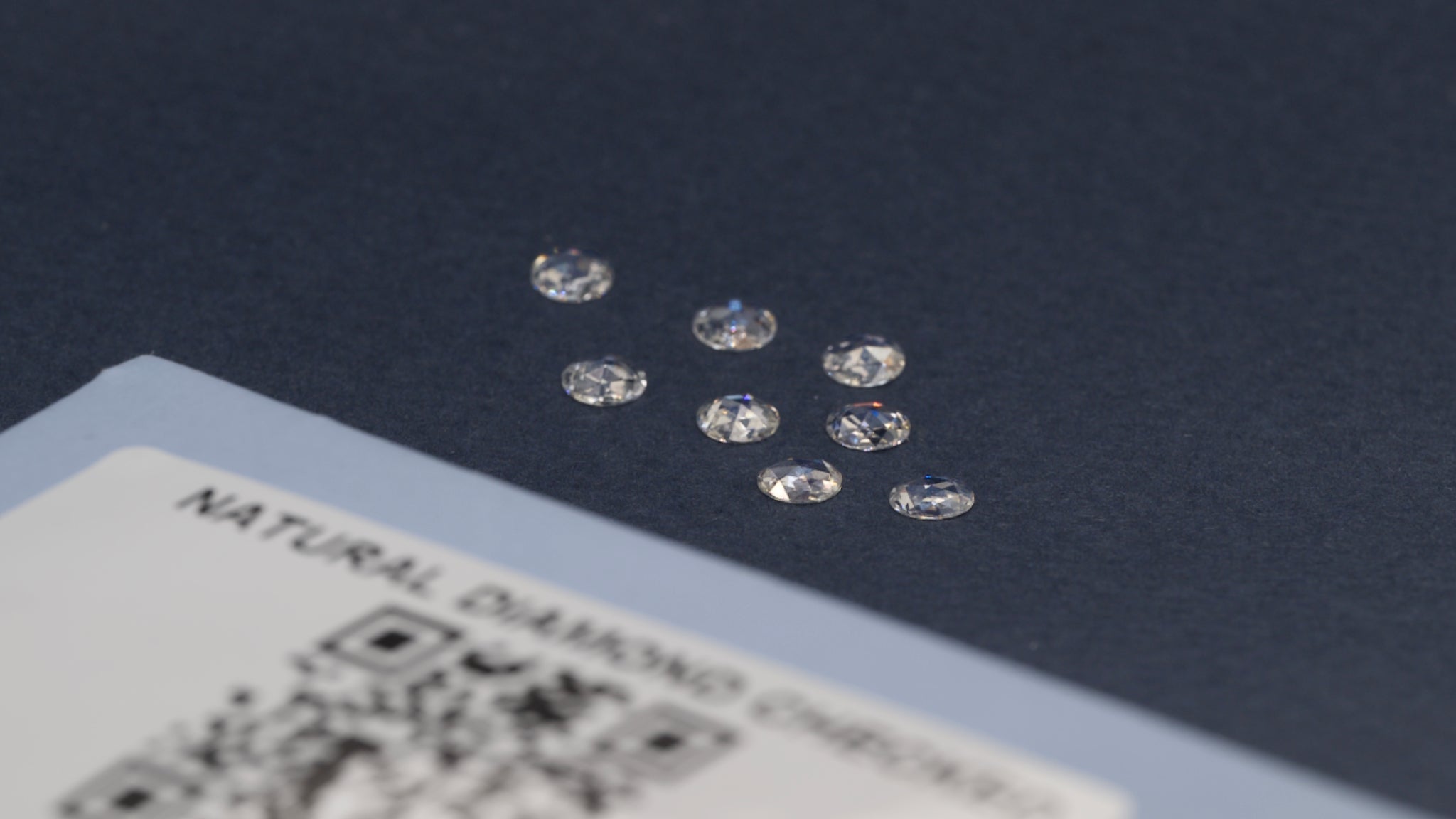

This has also triggered a second shift: natural diamond suppliers are increasingly certifying every parcel, no matter how small. Small diamonds (melée) that once travelled without paperwork now arrive with QR-coded reports proving natural origin. Ironically, the flood of labs has forced natural producers to raise standards of transparency and traceability — a development that benefits jewellers and clients alike.

Names Matter: Synthetic vs Lab Grown

Another transformation is in nomenclature. In gemmology, synthetic is the correct term for a laboratory-created gemstone that is chemically, optically, and physically identical to its natural counterpart. A synthetic ruby is still ruby, a synthetic sapphire is still sapphire — and a synthetic diamond is still diamond.

Marketing language has leaned heavily on the term lab-grown, softening the perception of “synthetic.” But regulators are pushing back. In France, for example, only natural stones may be called “diamond.” Anything created in a factory must be sold as diamant de synthèse (synthetic diamond). Simulants such as cubic zirconia and moissanite remain a different category altogether — materials designed merely to look like diamonds, without sharing their chemical structure.

Adding to this shift, the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) no longer grades laboratory-grown diamonds on the same scale used for natural stones. Instead, they apply descriptive categories such as Standard or Premium, underscoring the distinction between natural rarity and factory production.

This return to precise terminology matters. Clarity of language leads to clarity in the marketplace.

Sustainability: A complicated Story

Sustainability: A complicated Story One of the strongest selling points of lab-grown diamonds has been their claim to eco-friendliness. The logic seems sound: no deep mining, no vast holes in the earth, no disruption of water supplies. But the reality is more complex.

Diamond-growing machines require enormous, constant energy, along with steel and specialised facilities. Over half of the world’s production is based in China and India, where coal remains the primary power source. While in theory lab production could be run entirely on renewables, in practice much of it is not.

Meanwhile, natural diamond mining carries its own environmental burdens, but also sustains human communities. Around 10 million people worldwide depend on the diamond industry for their livelihoods. In Africa alone, diamonds contribute more than US$8 billion annually to local economies.

In Botswana, diamond revenues have funded free education for every child through to university — a powerful reminder that natural diamonds can be a force for national development as well as personal adornment.

Unlike gold, diamonds require no chemical extraction — only labour, often artisanal. This informal sector is highly vulnerable to exploitation and corruption, but new technologies are offering hope. Blockchain systems are being trialled to create incorruptible traceability, allowing small miners to sell diamonds legitimately at fair prices.

No conservation organisation has yet endorsed lab-grown diamonds as the greener choice. For now, lab diamonds trade on the promise of sustainability, while natural diamonds are proving it through evolving standards, transparency, and community impact.

Natural Diamonds: Billions of Years in the Making

Natural diamonds are elemental carbon transformed by intense pressure and heat between 1 and 3 billion years ago. Trace impurities of nitrogen, sulphur, or boron create the colours we treasure — yellow, blue, green, and beyond. Their formation predates human history, linking each gem to the deep past of the earth itself.

Lab diamonds, by contrast, begin with a seed of natural diamond and grow in a machine over days or weeks. They are chemically identical, but they lack the rarity of geological time. Some factories now experiment with unusual colours never seen in nature, or even with diamonds made from human or pet ashes. Yet the process, however imaginative, is industrial. It creates reproducible products, not singular miracles.

The Luxury Divide

How do the great jewellery houses position themselves?

Tiffany & Co. state openly that they do not consider lab-grown diamonds a luxury material. Cartier echo this sentiment, noting that natural diamonds carry history, while lab diamonds, created only weeks earlier, do not. “We make a promise of naturality and traceability to our clients,” they affirm.

Pandora, by contrast, has fully embraced lab-grown, with the aim of making diamonds affordable to customers who previously could not afford them.

These positions reveal the divide: for luxury houses, rarity and story are non-negotiable; for mass-market brands, accessibility is the goal.

What It Means for Jewellery

In fine jewellery, value is not only material but emotional. A jewel must be authentic, enduring, and worthy of inheritance. Lab diamonds may sparkle, but their resale value is negligible and their story short. Natural diamonds retain their rarity and their connection to human and geological history.

For Vermilion, the choice is not a choice at all. Our jewellery is artisan and artistic — a marriage of craftsmanship and authenticity. Lab diamonds, however tempting in cost, cannot belong in this vision. Instead, we are increasingly turning to the antique gleam of rose-cut diamonds, each parcel certified natural, each stone carrying the weight of history to further differentiate our design.

Conclusion: Clarity and Provenance

Both lab-grown and natural diamonds are here to stay. Each has its uses, and each appeals to different buyers. But in the world of fine jewellery, where artistry, permanence, and authenticity are paramount, natural diamonds hold the future.

The oversupply of labs has, paradoxically, given natural diamonds a gift: better certification, clearer traceability, and new technologies that protect even the smallest stones. Customers can now ask harder questions — and the industry is being forced to respond with greater transparency.

At Vermilion, we celebrate this clarity. Our jewels will increasingly be made with natural rose cuts — antique in look, modern in assurance, eternal in beauty.

Read more

Sapphires to kick off Spring After Nature perfected the solitary green hue with August's peridot, she went riotous for Spring (well at least in the Southern Hemisphere) with the gemstone sapphire ...

If you were born in October you are fortunate indeed – your birthstone is tourmaline, one of the most versatile and dazzling gems in the mineral kingdom. Each colour carries its own resonance, mak...